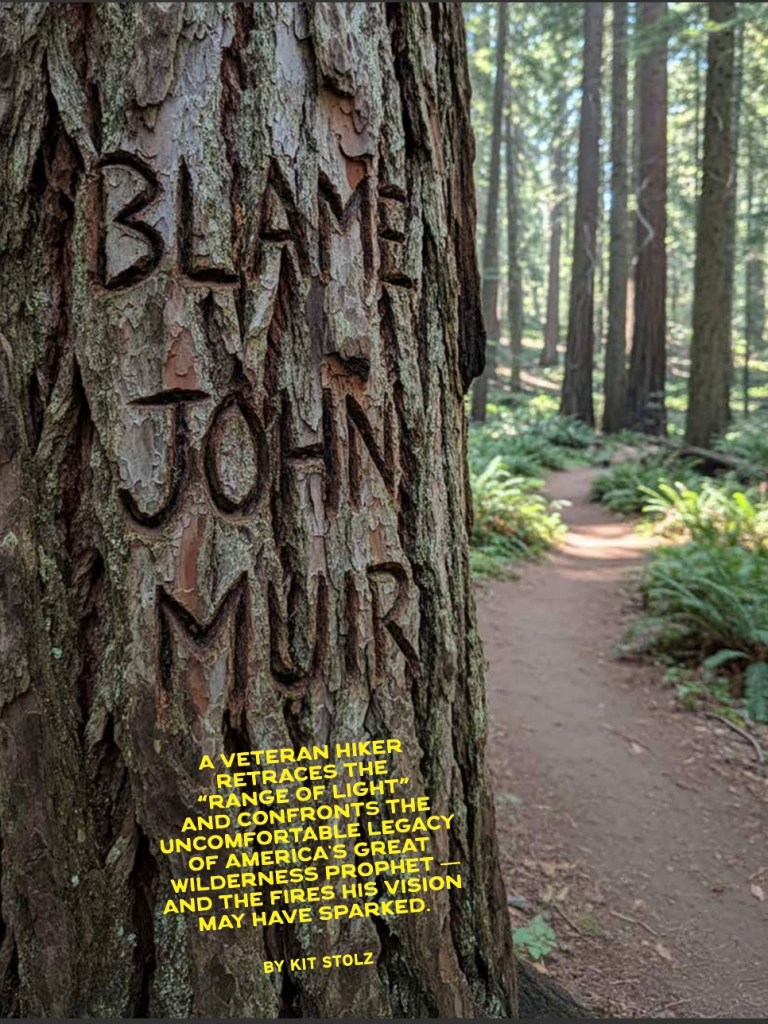

Here’s a story in Ojai Quarterly about my struggle with the legacy of my long-time hero John Muir while walking his trail — in smoke — this past September.

[This first image comes from the story in the winter issue of the magazine, as linked above, and has a slightly different tone and fewer pictures than this blogger’s version of the same story. FYI. Bloggers need not worry about column inches.]

As I plod at first light up the legendarily difficult “Golden Staircase” towards Mather Pass, panting, pushing down on my hiking poles for a little extra oomph, with five miles and thousands of feet still to go to reach the crest, I wonder what in the world has come over me.

What kind of spirit is this? What has possessed me to try this — at seventy?

In my chest I feel my heart pound. A fiery ache fills my watery legs. Every few minutes I look around for a flat-topped boulder on which to sit, rest the weight of the pack, catch my breath, let my thudding pulse slow. I stop often this way, to nod and smile perhaps a little wryly at the occasional younger backpackers who pass me by.

I blame John Muir. Were it not for Muir; for his captivating adventures, for his inspiring and oft-quoted words about his beloved “Range of Light,” I wouldn’t be here. Trying to walk 212 utterly exhausting miles through the High Sierra — in smoke.

The Sierra National Forest, fifty miles to the south, was on fire. And for that too — some say — John Muir is to blame.

I flashback forty years. With my young family — a thirtysomething partner and a twosomething child — I visit a tiny luggage store next to the Vista Theater in Los Angeles to buy a suitcase for a trip. On a high shelf behind the sole proprietor stands a dozen or so travel books for exotic and pricey vacation locales, including one wildly out of place — “My First Summer in the Sierra,” by John Muir. I buy it on impulse, remembering a handful of blissful times in my youth in the mountains. Upon reading I find myself plunged into the raw beauty of the Sierra once again. A different, wilder life awaits me. If I want it. I search out more of Muir’s writing and hear the mountains calling him. I hear that call too.

“Camp out among the grass and gentians of glacier meadows, in craggy garden nooks full of Nature’s darlings. Climb the mountains and get their good tidings,” Muir wrote in 1898. “Nature’s peace will flow into you as sunshine flows into trees. The winds will blow their own freshness into you, and the storms their energy, while cares will drop off like autumn leaves.”

Living in smoggy, chaotic, traffic-choked Los Angeles in the late 80’s and early 90’s, I needed that natural peace. Eventually I went to the mountains to look for it, even walking the JMT in a heavy snow year in 1995, thirty years ago. As countless others go to the mountains today, perhaps equally “over-civilized,” people who find they need wildness and beauty and adventure in their lives, (And as did countless others in the late 19th century, about as many women as men, who united to form the Sierra Club, which Muir launched in 1892 “to explore, enjoy, and protect wild places.”)

So perhaps I should credit John Muir and his allies. Had they not spent decades expanding the national parks and forests, building trails, blocking planned roads through the mountains, expanding forest protections, the John Muir Trail, or JMT, wouldn’t be here. Exhausting me.

Flash back a few days, to September 3. With a friend from days spent on the Appalachian and Pacific Crest Trails, I head south from Tuolumne Meadows. We’re left gasping in the thin air on the first steep climb, but a night later recover under a full moon by Thousand-Island Lake.

After four days and a stay at a hiker’s cabin in funky-but-friendly Red’s Meadow — about fifty miles south of Yosemite — we turn up the JMT again, energized but troubled by reports of a major fire fifty miles to the south. Dingy blue-grey wisps of smoke hang in the trees.

The smoke came from the Garnet Fire, which — following lightning strikes — had broken out a little over two weeks before in Sierran forests east of Fresno. The fire burned for almost a month with catastrophic intensity, consuming about 60,000 mostly uninhabited acres of old growth forest. This is the sort of forest fire which some experts blame on, yes, John Muir.

DID MUIR”S VISION OF WILDERNESS BRING ENORMOUS FIRE TO THE SIERRA?

“To solve the wildfire crisis, we have to let the myth of “the wild” die,” was the headline on a story in August in the L.A. Times by reporter Noah Haggerty. In a story published just days before the Garnet Fire broke out, Haggerty wrote that “Muir sold the president [Teddy Roosevelt] on a uniquely American myth of the wilderness — that if we work hard enough to isolate public lands from our influence, we can preserve a landscape essentially “untouched” by man.”

Haggerty in his news story interviewed fire ecologists and indigenous fire experts working to bring beneficial “good fire” back to Sierran forests. The idea is to reduce fuel for wildfires to prevent an all-consuming wildfire. The Garnet Fire is the sort of inferno that has destroyed millions of acres of forest in California in the last five years, in dozens of uncontrollable fires, many of them — such as the Camp Fire that killed 85 people in Paradise — lethal.

Muir in 1903 on a famous camping trip in Yosemite with Teddy Roosevelt convinced the President to put Yosemite under federal protection. With this protection came a vision of wilderness untouched by man, implicitly (if unwittingly) excluding the first peoples who lived there. This prevented native peoples from “tending the wild” with frequent low-intensity fires, all but guaranteeing the destruction of forests, when the suppressed fires came the next time.

“The single most important reason mentioned by Native American elders when asked why their ancestors burned the Sierra Nevada was to keep the underbrush down to prevent a large, devastating fire,” writes M. Kat Anderson, a leading researcher of indigenous land-management techniques used in the Sierra. In a report to Congress in 1996, she documents that in the 500 years before 1800, as many as 100,000 Indians lived in the Sierra, and the burning, tilling, seeding and other tools used by residents in over 2500 native villages had an enormous and beneficial impact, making forests sustainable, as they cannot be if left entirely untouched.

It’s a powerful critique of Muir’s vision of a wilderness untouched by man. It’s a fact that Muir’s desire to protect forests from man — and loggers — shaped Teddy Roosevelt’s thinking about public lands. It’s true that Muir’s idea of “the wild” as a place apart from man proved short-sighted, because it assumed that Sierran forests would not need tending.

But it’s also true that the federal government didn’t take control of the management of Sierran forests for many decades after the Gold Rush, well into the 20th century for most such forests, and long after — tragically — the native peoples, such as the Yokuts and the Mono that “tended the wild” in Sierran forests had been decimated.

Fire ecologists know what happened in the forests that burned in the Garnet Fire because in these Sierra National Forest lands stands the Teakettle Experimental Forest, a block of about 3000 acres used for the past century to study and test forest management techniques. A meticulous fire scar study of the Teakettle forest showed that before 1865, fires in the Teakettle were frequent, occurring in the range of every 11-17 years, presumably started by native peoples. No major fire occurred after 1865 was detected when the study was conducted — none until this year.

Muir has been blamed for many sins, including racist remarks about people of color in his early years, even if he argued forcefully and at length against the eradication of Indians (when that was California state policy — a $5 bounty for Indian scalps –in the19th-century). One can blame him for not realizing that the “gentle wilderness” he so admired in the Sierra forests was the work of the first peoples, and needed their tending. Yet when indigenous “good fire” in the Sierra National Forest came to an end, Muir was working as a young inventor in a broom factory in Ontario, Canada. He had yet to even see California. He had nothing to do with the decimation of the 90,000 first peoples who lived for centuries in Sierran forests, a great number of whom were felled by European diseases in the 1830’s. To blame John Muir for the genocide of California tribes, not to mention for forest management policy a hundred years after his death, makes little sense.

Kim Stanley Robinson, the author of “The Sierra Nevada: A Love Letter,” has come to Muir’s defense, with several other California writers. He points out that Muir never advocated for the removal of native peoples from the land in anything he wrote, even in unpublished letters or journals. Further, exploring coastal mountains in Alaska in later years, Muir lived for a time with the Tlingit people. As a child Muir had been nearly worked to death by his father,and often beaten. For that reason he greatly admired the respect these people showed their children.

“I have never yet seen a child ill-used even to the extent of an angry word,” Muir wrote. “Scolding, so common a curse of the degraded Christian countries, is not known here at all. But on the contrary the young are fondled and indulged without being spoiled.”

Regarding the Garnet Fire, Matthew Hurteau, a fire ecologist, published in early September an impassioned piece called Eulogy for the Teakettle, in which he mourned the loss of the grand old growth forest to which he had devoted two decades worth of his work and life. The tragedy for Hurteau — and the Sierra National Forest — is that he and his colleagues over several years put together a treatment plan to reduce the risk of a catastrophic fire in a large and ancient forest.

Despite bureaucratic opposition, a government shutdown, and management changes, in 2018 they won a $896.000 CalFire grant for prescribed burns for most of the 3,000-acre old growth Teakettle forest. These treatments were meant to save the forest. After countless delays, they were scheduled to begin in the fall.

“I cried on September 1,” wrote Hurteau. “I am sad and angry. I am sad because this old-growth forest is no more. I am angry because this outcome was a choice. The choice was inaction by forest “leadership.” They chose doing nothing instead of working to prepare these incredible trees that are hundreds of years old and some as much as 9 feet in diameter.”

I had read reporter Haggerty’s accusatory piece in the L.A. Times before I started on the JMT. Although most analysts don’t blame Muir for the “Smokey Bear” policy of fire suppression — which became official Forest Service policy after WWII — it’s widely accepted among foresters that this policy has failed. In 2007, two researchers with the USDA (which oversees the Forest Service) published a white paper called “Be Careful What You WIsh For: the Legacy of Smokey Bear,” pointing out that “the long-standing policy of aggressive wildfire suppression has contributed to a decline in forest health, an increase in fuel loads in some forests, and wildfires that are more difficult and expensive to control.”

Still, the possibility that my hero — the man whose signature I had tattooed into the inside of my forearm — could have even inadvertently caused such ruin unsettled me. Would these fires spoil the Sierra? Would I come to dread this trail?

Lose faith in Muir?

I walked southbound, a little more hesitantly, towards Evolution Valley, I had in mind what a Hawaiian-shirted backpacker told me when we encountered him and a friend on the trail. They were heading out, cutting their trip short, and he told me why.

“I don’t want to have to see Evolution Valley in smoke,” he said. “I don’t want to remember it that way.”

Days later I reached the famously beautiful Evolution Valley. The valley, as paradisical as any in the Sierra, was shadowed by orangeish clouds flowing into the valley and building up against the peaks. Blessedly, these same clouds that night brought rain, washing the air.

The precipitation resumed late the next day, as I panted my way up out of Evolution Valley to Evolution Basin, a thousand feet higher, but this time it came as hail and hardened snow. I hastily put up the tent. After a freezing night, the air at dawn could not have been cleaner. The grand views went on and on and into memory.

The renovated Muir Hut atop Muir Pass serves as a portal to the higher and much more challenging JMT in the Southern Sierra. Each of the next five 12,000-foot passes on the southern JMT took me a half day or more to climb, and as I made my way slowly up the switchbacks, I forgot my worries about smoke. In their long history, these rocky mounts have seen far worse — ice ages, avalanches, monumental floods — and recovered every time.

“By forces seemingly antagonistic and destructive Nature accomplishes her beneficent designs — now a flood of fire, now a flood of water; and again in the fullness of time an outburst of organic life,” wrote Muir, about Mt Shasta.

He could easily have been describing the timelessness of the Sierra. A few days of smoke cannot ruin these mountains, any more than a few crashing waves can ruin a beach.

I headed up the all-but-endless climb up the Golden Staircase, a path that steepens pitilessly towards the top of the glacial canyon and Mather Pass. After seven hours or so I at last crested the final rise and collapsed at the top, on a tiny beach near an outlet stream. Rethinking my allegiance to this trail.

Robinson too, as much as he adored the Sierra and admired John Muir, had no such affection for the JMT.

“Have I mentioned that I don’t like the John Muir Trail?” writes Robinson snarkily in his “The Sierra Nevada: A Love Story.”

“The Interstate 5 of the Sierra, the crowd scene, the foot killer, the permit sucker? The 212 miles of nonstop human busyness?”

Four days later, when on my way out I crossed over the Sierra crest on Kearsarge Pass in Onion Valley, the last of the high passes on my route, I decided in my weariness that he had a point.

One can experience the Sierra in all its glory without spending weeks on the Muir Trail. Muir himself often wrote of a day chasing a butterfly, or hours spent counting the tiny flowers in a yard-square of mountain meadow, or of simply strolling along in the sunshine.

“Hiking — I don’t like either the word or the thing,” he wrote in 1911. “People ought to saunter in the mountains, not hike.”