The Partial Nuclear Meltdown That Still Haunts Ventura County

Here’s a new story I wrote for Ojai magazine on — believe it or not — a major nuclear accident, a partial nuclear meltdown, that still contaminates part of Ventura County.

‘Woody Guthrie used to say that some men will rob you with a six-gun, and some with a fountain pen. The killing today at SSFL is done by burying contaminant numbers in a table that you need a magnifying glass to read. And then lying about it.’

— Dan Hirsch

Imagine a vast but unseen menace, an invisible rain of infinitesimal particles — as likely to cause cancer in people as any substance — falling on a mountain ridge in northeast Ventura County, then moving over Simi Valley, Canoga Park, the San Fernando Valley and into Los Angeles.

Imagine companies with government contracts responsible for this rain of ghostly mutagens working with government officials to keep this mortal threat a secret from the public.

Imagine the executives responsible for the unseen downpour not only refusing to reveal it, but when confronted with indisputable films and records of its occurrence, flatly denying it.

This was an era — the 1950s and ’60s — before environmental review. Almost the only notice taken in the newspapers of a massive nuclear and rocketry facility in the mountains over Simi Valley called the Santa Susana Field Lab were the want ads that attracted thousands of workers. Mostly those hired were blue-collar workers paid well to work in aerospace.

But tens of thousands of rocket tests, and decades of nuclear waste in Ventura and Los Angeles counties, left behind radioactive particles, toxic chemicals, and radioactive metal in industrial recycling centers in Ventura, and as well in the waters off Santa Cruz Island. In all these places remain some of the most toxic substances known to humankind, and in some cases, in massive quantities deposited there with little or no public notice or remediation.

Now imagine one University of California nuclear expert, volunteering for years of organizing and investigation, uninterested in personal fame, relying on a tiny circle of fellow activists and the support they inspire from student researchers, stepping forward and breaking that story’s tomb-like silence.

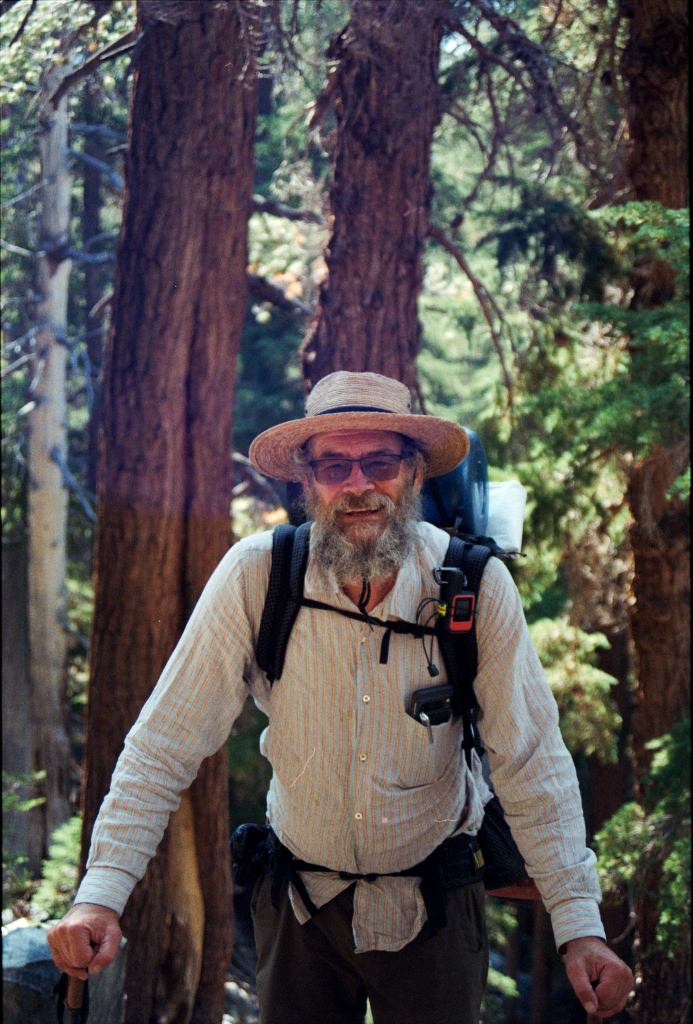

To this day, Dan Hirsch, even in retirement, while living near UC Santa Cruz, remains at the heart of the long battle between the owners of the facility — which permanently closed in 2006 — and the activists demanding a complete cleanup of its toxicity, both radiological and chemical.

This is the story of the Santa Susana Field Lab. It has been a source of fierce contention and countless lawsuits and scientific studies for decades, but might never have come to light if UCLA nuclear policy lecturer Hirsch, working with fellow anti-nuclear activists, student investigators and the press, had not revealed the truth of the partial nuclear meltdown in 1979.

THE MELTDOWN

“This is my first opportunity to tell what happened in 35 years,” said John Pace, who was 20 when he started working as a reactor operator trainee at the console of the Sodium Reactor Experiment (SRE) at the SSFL. “I was not supposed to say a word.”

Pace returned to Southern California from retirement in Idaho in 2014 to speak at an event hosted by Hirsch’s community SSFL Work Group in Simi Valley. After holding a decades-long silence about the accident, as ordered in 1959, Pace was overcome with emotion and apologized to the crowd while telling his story. The crowd included other former SSFL workers, some of whom — like Pace — had had health problems since their work tenure.

Pace told reporters he was sterile for seven years after a few years of work at the SSFL, and later developed lung problems and skin cancer, which he attributed to his time working in the reactor building.

The reactor at which Pace worked in his youth — the SRE — was the largest in Southern California at the time. But at 20,200 kilowatts, it was small by modern standards and primitive in design. The SRE lacked any sort of concrete containment dome, which now is a design standard in reactors, to prevent any release of radioactivity from inside the structure to the atmosphere.

Pace was a trainee reactor operator, but had been on the job only a few months. He admitted to being intimidated by older, more experienced officials at the plant. When he arrived for his shift on July 12, 1959, he was shocked to hear what the reactor officials said.

“There were men all lined up around the console, and they started discussing what happened with the accident,” he said. “As I stood there and listened, they scared me to death with what they were talking about, because a ‘power excursion’ is the worst thing that can happen in a reactor.”

For reasons the operators didn’t understand at the time, the nuclear reaction — and internal temperatures — in the uranium core escalated uncontrollably in a fraction of a second. During this “power excursion” and over the following 13 days, nearly one-third of the radioactive fuel rods melted, and dozens of fuel rods broke inside the reactor chamber.

“I heard about how they had barely shut the reactor down after it had run away on them,” Pace said. “The reactor had an automatic shutdown, but that didn’t work and then they finally did it mechanically, powering the control rods down. All this went on for quite a while, and the storage tanks filled with radiation, and they realized they couldn’t do anything about it. I was there to listen as they said that if we don’t shut this down, it’s going to blow up. And so they had to release the radiation straight out of the reactor into the atmosphere. This has not been talked about, but the winds were blowing in the direction of the San Fernando Valley.”

The reactor officials, puzzled by what went wrong, restarted the reactor two hours later. Some radiation monitors went “off scale,” according to Atomic Energy Commission records, and an on-site health-monitoring official later reported that radiation inside the reactor building had reached 300 times safe levels.

Pace said a fellow employee asked the company’s top executive, Marvin J. Fox, if they could tell their wives about the radiation then “over their heads” in nearby towns such as Chatsworth, Canoga Park and Simi Valley. After a moment’s consultation with aides, Fox came back with a stern warning.

“They said no, you cannot — we don’t want anybody saying a word about it,” the director said. “We’ll report what happened to the public in our own due time.”

The reactor workers were subsequently sworn to silence. Other SSFL workers spoke of being threatened with legal action, and of having dosimeter badges (which measure employees’ work exposure to radiation) confiscated. Because of the threats, which Pace said had a military tone, for decades SSFL workers loyally stayed silent, even at the risk to their own health and their families.

Two hours after the partial nuclear meltdown, officials restarted the badly malfunctioning reactor.

“It was a very foolish thing,” Pace said. “It scared us to death, but for two weeks, every 24 hours, they would shut down the reactor and then restart it until they figured out for sure that the sodium pump was the cause. Every time they shut down the reactor, more radiation was released out into the atmosphere. It could have been toward Simi Valley, or Topanga Canyon. I can’t tell you which way it went.”

For Hirsch, it’s no mystery why the reactor operators ignored safety precautions.

“Is it really hard to understand?” he asks. “No, not at all. They were up on a hill. No one could see them. It was before the days of any regulation. The EPA didn’t exist. And they were nuclear cowboys.”

Weeks after the partial meltdown, Atomics International — on the letterhead of the Atomic Energy Commission in Washington, D.C. — released on a Saturday morning in Canoga Park a brief statement saying that a single “parted fuel element” had been observed at the reactor.

“The fuel element damage is not an indication of unsafe reactor conditions,” according to the statement. “No release of radioactive materials to the plant or its environs occurred and operating personnel were not exposed to harmful conditions.”

No reporter followed up on the press release. Although the Santa Susana Field Lab (and supporting facilities in the San Fernando Valley) employed thousands of workers for decades in dangerous conditions, with injuries and a few deadly accidents, still nothing of the meltdown was reported for 20 years until Hirsch — working with UCLA students in the 1970s — began requesting documents from the Atomic Energy Commission under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA).

OPPOSING VOICES

Today, Hirsch and his many allies in Ventura County and around the state, most prominently Melissa Bumstead and Jeni Knack, co-founders of the Parents Against SSFL activist group in Simi Valley, believe that unless legal action is soon taken against the powers that be at the site — Boeing and the state Department of Toxic Substances Control — the alleged collusion will succeed, allowing Boeing to avoid the costs of a full-scale cleanup, expected to cost hundreds of millions of dollars, leaving residents below the site in Simi Valley and West Hills at risk.

Without Hirsch’s leadership — detractors and supporters such as Bumstead agree — the fate of the Santa Susana Field Lab over the last 60 years would have played out very differently.

Phil Rutherford, a Boeing consultant and nuclear expert who worked at the SSFL as senior manager of Radiation Safety for 25 years, overseeing 10 employees, argues (1) that no contamination has been found beyond the boundaries of the 2,850-acre site. He said that any cancer among residents in Simi Valley was not caused by the SSFL, and has questioned the need for a “cleanup to background.” Although he makes clear he does not speak now for Boeing — which limits its engagement with the press to corporate statements — in his detailed analysis, he blames Hirsch for prolonging the struggle over the cleanup.

Rutherford commented (2)) last year: “With the exception of Boeing’s successful SB 990 lawsuit against the state, all lawsuits have been initiated by Dan Hirsch and other activist organizations against the California Department of Public Health, DTSC itself, the Department of Energy, and Boeing. Since Dan Hirsch was not a party in the mediation and not a signatory to the [2022] Settlement Agreement, there is no guarantee that future lawsuits will not occur if things do not go as he wants.”

This stance ignores the substantial evidence of elevated rates of cancer found among the people of Simi Valley, among other towns near the SSFL. In 2007, a federally funded study (3) by a University of Michigan epidemiologist found that specific cancer incidence rates were 60% higher for residents living within two miles of the site, compared to five miles away.

Bumstead of Parents Against SSFL said that the state agency refuses to take these numbers into account.

“The DTSC won’t recognize outside reports, even when they’re federally funded, like the 60% higher incidence rate,” Bumstead said. She speaks with a weary familiarity of cancer. Her daughter Grace’s cancer was diagnosed when Grace was 4 years old. The second diagnosis — well after her daughter’s first recovery — came when Bumstead and her husband had for a time hoped to move the family away, out of state, away from the SSFL, only to realize they could not support their sick child without their local families’ help.

In the course of her families’ long trial by sickness, Bumstead said she has met in oncologists’ offices dozens of other local families with kids with cancer. In meetings and demonstrations, she displays a bulletin board with pictures of local children in cancer treatment. It’s one reason she speaks harshly of the DTSC and Boeing and what she calls their attempt “to kick the can down the road for a thousand years.”

In an attempt to resolve the controversy, Gov. Gavin Newsom, Jared Blumenfeld, secretary of the California Environmental Protection Agency, and Meredith Williams, director of the DTSC, announced a new plan, based on a legal settlement reached behind closed doors between Boeing and the DTSC in May 2022, that they say will at last decontaminate the SSFL.

“Santa Susana Field Lab is one of our nation’s most high-profile and contentious toxic cleanup sites,” said Newsom in a press statement. “For decades there have been too many disputes and not enough cleanup. Today’s settlement prioritizes human health and the environment and holds Boeing to account for its cleanup.”

But Hirsch and his long-term allies, including Parents Against SSFL, Physicians for Social Responsibility, and the Natural Resources Defense Council, believe the settlement gives Boeing license to avoid the vast majority of the cleanup — up to 94%. Although the clock is running, the advocates — possibly with the county of Ventura and other local governments — want to sue.

On Jan. 12 of this year, the Ventura County Board of Supervisors announced a “tolling agreement” between Boeing, DTSC, and nearby local governments — the cities of Los Angeles and Simi Valley, as well as Los Angeles and Ventura counties.

The agreement removed the need for the local governments — or other entities — to file suit by Jan. 15, 2024, against Boeing and the DTSC, under the California Environmental Quality Act.

The concern is that the agreement could narrow lawsuits over the cleanup to individual “Cleanup Plans” for smaller portions of the site, 10% or less, which advocates say will greatly limit the extent of the cleanup to measures limited numerically in the Settlement Agreement of 2022.

“Woody Guthrie used to say that some men will rob you with a six-gun, and some with a fountain pen,” Hirsch said. “The killing today at SSFL is done by burying contaminant numbers in a table that you need a magnifying glass to read. And then lying about it.”

Hirsch is a singular figure — a hardworking and largely unpaid Gandhi-inspired idealist. As an undergrad at Harvard in 1970, Hirsch helped lead protests against the Nixon administration’s assault on Cambodia, ultimately closing the campus to allow students to go home to organize against the war. Hirsch returned to his hometown of Los Angeles in 1972 and — after finding work as a lecturer at UCLA in nonviolence and energy policy — launched a campus Committee to Bridge the Gap (CBG) to peacefully end the war in Vietnam.

After the war ended in 1975, Hirsch, with CBG, turned his focus to nuclear weapons and policy, discovering, to his shock, at the UCLA campus near his office a working nuclear reactor emitting radioactive gasses. This stunner motivated students on campus to volunteer to join CBG’s investigatory work. Besides the reactor on campus, they soon found records of an unlicensed and unmarked nuclear waste dump on the grounds of the nearby Veterans Administration.

These nuclear discoveries made headlines, and the CBG was ultimately able to challenge the relicensing of the campus reactor and win its removal. At his modest log cabin home in the redwood forest not far from UC Santa Cruz, where he led a nuclear policy center for decades after his time at UCLA, Hirsch keeps a part of the reactor console given to him as a sort of prize in the end by UCLA officials. It is kept in one of several storage sheds full of decades of files.

BREAKING THE SECRET MELTDOWN STORY

In 1979, just two weeks after a partial meltdown of the Unit 2 reactor at Three Mile Island caused a near panic in Pennsylvania, and about a month after the unwittingly well-timed release of the nuclear-reactor disaster film “The China Syndrome,” Warren Olney on his popular nightly NBC Channel 4 newscast shocked Los Angeles with news of a partial nuclear-reactor meltdown above Simi Valley in 1959.

“In 1979, when we discovered the partial meltdown, I brought the story to Warren and he did a five-part series during ‘sweeps week’ for the ratings,” Hirsch said. “They took out a half-page ad in the LA Times and really promoted the series.”

This brief summation dramatically understates the investigatory work that Hirsch and a mentee, Michael Rose, did in the AEC archives at UCLA, and with FOIA requests to pry documents, images, and even films loose from the nuclear repository in Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

“I think he deserves a lot of credit, and he has been willing to take the heat for it,” Olney said in an interview in the fall. “It’s remarkable. The video images showing the fuel rods broken inside the reactor were just incredible. He always gives credit to a student documentarian he worked with, Michael Rose, for the images, but they were a gold mine. He and his team got these videos from the NRC (Nuclear Regulatory Commission). I’m sure you can never get anything like that anymore.”

Olney adds that despite abundant evidence of a catastrophic meltdown at the SRE — including the fact that it took millions of dollars, the design of a new system of cameras and grappling tools to work inside the reactor chamber, and 14 months of unprecedented work to remove the broken core and repair the malfunctioning cooling system — Atomics International executives said nothing much had gone wrong.

“It did not appear to be a hazard to the public or to our employees, and in retrospect it wasn’t a hazard to the public or our employees, and we put that plant back online,” said Atomics International Assistant General Manager Wayne Myers to Olney in the NBC series.

That statement was as false and misleading as the original press release. This past fall, a nationally recognized expert in nuclear reactors, Arnie Gundersen, who has conducted radiological studies at the SSFL, said that the partial nuclear-reactor meltdown released many more radioactive particles than the much-better-known partial meltdown at a reactor on Three Mile Island in 1979.

“I would say the release [of radioactivity] from Santa Susana was definitely the worst meltdown up until Three Mile Island,” Gundersen said. “And there were actually more radioactive particles, such as cesium and strontium, that got out of Santa Susana than got out of Three Mile Island. Three Mile Island released a lot of noble gasses, such as xenon and krypton, at much higher rates, but the stuff that’s on the ground at Santa Susana, even now, is much worse than the stuff on the ground in and around Three Mile Island.”

For his part — when not organizing around Diablo Canyon and other nuclear facilities in California — Hirsch has devoted 45 years of his life to cleaning up Santa Susana. It’s one of few places in the world to have suffered fallout from a partial nuclear-reactor meltdown, he points out, and it’s also a site where tens of thousands of rocket tests were performed from the 1950s to the 1980s, resulting in the dumping of hundreds of thousands of gallons of carcinogens onto the ridgetop site, including hydrazine, perchlorate, and trichlorethylene.

“On the last day [of the NBC series], Warren got a call from a woman in Newbury Park, who was the mother of a child with childhood leukemia,” Hirsch said. “She said she had found eight other families in the neighborhood with kids with cancer. She asked Warren for help, and he said, ‘I’m a reporter — call Hirsch.’ So she called me to ask for help. And I promised to help her. I never thought it would take so long.”

DID THE STATE MISLEAD VENTURA COUNTY ADVOCATES AND OFFICIALS?

Hirsch and many of his longtime allies believe they have been misled and — in Hirsch’s case — personally betrayed by California officials, including former Cal EPA Secretary Jared Blumenfeld. He’s angry about it.

“We were played,” Hirsch says bitterly.

For decades Hirsch and allies have pushed for a “cleanup to background,” which means removing the radionuclides from the site, removing soil in massive volumes if necessary, and it means removing “Contaminants of Concern” from aquifers and keeping them out of stormwater.

For Hirsch and his many local allies, the painful part is that, first, in 2007, and then again in 2010, they believed they had won that prize — the cleanup to background — in a pair of binding legal agreements, known as the Administrative Orders of Consent (AOC). The cleanup was expected to be complete by 2017.

“There was literally dancing in the streets when we heard that we had gotten an agreement for a full cleanup,” Hirsch said. “We really thought that by 2017, we would be home free. And I can tell you about the depression people who live near the site felt — people who’d seen their kids grow up without a cleanup, and now are seeing their grandchildren grow up without a cleanup.”

Despite Hirsch’s unofficial position, his grasp of the complex radiological issues and the clarity of his presentations have repeatedly put him at the center of SSFL controversy. Often, he has found himself in negotiations over technical cleanup standards with state and federal officials, including more than one Cal EPA secretary, as well as DTSC Director Meredith Williams.

Hirsch said that when Blumenfeld was first appointed head of California’s EPA agency by Gov. Newsom in 2019, he searched out Hirsch regarding the SSFL, worked with him for months, even asking him to prepare “an action memoranda” regarding negotiations. Blumenfeld promised to retain the standardized risk assessment — which controls the extent of the cleanup — and said that he would defend the AOC agreements.

“This is what Jared had promised to me, and had boasted to me,” Hirsch said. “He said he told Boeing, ‘We ain’t going to do it.’ He also told the public and Sen. Padilla and numerous mayors and supervisors that we’re not going to touch the risk assessment, we’re not going to weaken it and, well, that’s exactly what they ended up doing.”

CAL EPA OFFICIAL ALLEGEDLY MISLEADS SIMI VALLEY CLEANUP ADVOCATES

In 2020, after extensive work with Hirsch, Blumenfeld came to Simi Valley to give a talk, (5) in which he specifically thanked Hirsch and Bumstead and then-Ventura County Supervisor Linda Parks, among others, for their work attempting to hold regulators to account.

“What we have in front of us are agreements,” he said, speaking of the 2007 and 2010 legal agreements to clean up the Santa Susana Field Lab lands and water to a pristine state before the rocket tests and nuclear reactor accidents.

“We’re not really here to negotiate, this is not negotiation,” Blumenfeld said. “This is about implementation.”

That was in 2020, and at the time, Blumenfeld’s remarks — fulsome in their praise for Hirsch and other advocates — were warmly applauded by a receptive Simi Valley crowd.

But in 2021, the same DTSC that Blumenfeld chided for dragging its feet on the cleanup went into closed-door negotiations with Boeing, emerging nine months later with a Settlement Agreement in 2022 that Hirsch and Ojai water-quality expert Larry Yee, among others, say means that most of the toxins at Santa Susana will remain.

Yee, who served from 2012 to May 2022 on the Los Angeles Regional Water Quality Control Board, which regulates stormwater and toxic waste runoff from Santa Susana, expressed serious concerns at the time about the closed-door negotiations leading to the 2022 Settlement Agreement between Boeing and the DTSC. As a consequence, Yee said he believes he was forced to resign from the water board on a legal pretext created by Cal EPA officials before a crucial vote by the water board upholding the disputed Settlement Agreement. Like Hirsch, Yee feels personally wronged by Blumenfeld and the Newsom administration, but he calls for a lawsuit for the sake of the people downhill from the SSFL.

He joined with Hirsch and other advocates pressing Ventura County to file suit because, he said, “Without a complete cleanup, people continue to lie in harm’s way.”

“This is a divide-and-conquer strategy by Boeing and the DTSC,” Yee said. “Unlike the AOC agreements, which called for a full cleanup to background, the Settlement Agreement focuses on certain areas within the larger site — no more than 10% of the total.”

Hirsch agrees.

“Jared Blumenfeld made 1,000 pledges and broke every one of them,” Hirsch said. “And he did it on behalf of the polluter. And his actions, if not overturned, will result in a bunch of cancers. The system doesn’t work the way it’s supposed to. The agencies that are supposed to protect us are actually working with the polluters they’re supposed to be regulating.”

Today, local area governments — including Ventura and Los Angeles counties and the city of Simi Valley — are contemplating filing a lawsuit against the decades-long cleanup plan released by the Department of Toxic Substances Control in June 2023.

Ventura County Supervisor Matt LeVere, whose district includes Ojai and Ventura, said the Simi Valley City Council and Board of Supervisors for both Ventura and Los Angeles counties have agreed jointly to hire the Meyers Nave law firm and environmental assessment firm Formation Environmental LLC to look at the DTSC’s environmental review.

“I’m still fully committed to holding Boeing and the Department of Energy accountable,” LaVere said. “If our lawyers and consultants come back and tell us this is not a good agreement, that it’s not a full cleanup, if we think there’s some kind of sweetheart deal, then we will challenge it, because I absolutely believe, and my colleagues also believe, that there needs to be a full and exhaustive cleanup of this site. And if it takes filing a lawsuit to get that, we will.”

Hirsch for his part said he remains committed to the struggle to decontaminate Santa Susana, and is working with allies to file a lawsuit to challenge the Settlement Agreement between DTSC and Boeing, arguing that they are “begging to be sued.”

“The arc of the moral universe curves toward justice,” he said, referencing a famous saying of Martin Luther King Jr., but not accepting its passivity.

“The arc of the moral universe doesn’t curve on its own,” he said. “The arc of the moral universe curves toward justice, but sometimes it curves away. People have to work hard to curve the arc of the moral universe toward justice.”

FOOTNOTES:

1.

2. https://www.philrutherford.com/SSFL/Settlement_Agreement/DTSC-Boeing_Settlement_Agreement.pdf

3. https://www.ssflworkgroup.org/files/UofM-Rocketdyne-Epidemiologic-Study-Feb-2007-release.pdf

4.